Cim’s art practice contemporises a journey of reclaiming her First Nations mother’s stolen identity and how their relationship became a complexity of dreamlike scenarios, of startling discoveries and an extraordinary life together. Having obtained a Master of Visual Arts by Research at ECU in 2020, and a Photography and Arts degree prior, Cim now works out of a studio at Goolugatup/Heathcote and is also a member of the Swan River Print Studio. Painting, photography, printmaking, text, ceramics and archives constitute Cim’s multidisciplinary art practice that has become a lifelong search to piece together lost fragments of her Western Desert ancestral history and culture.

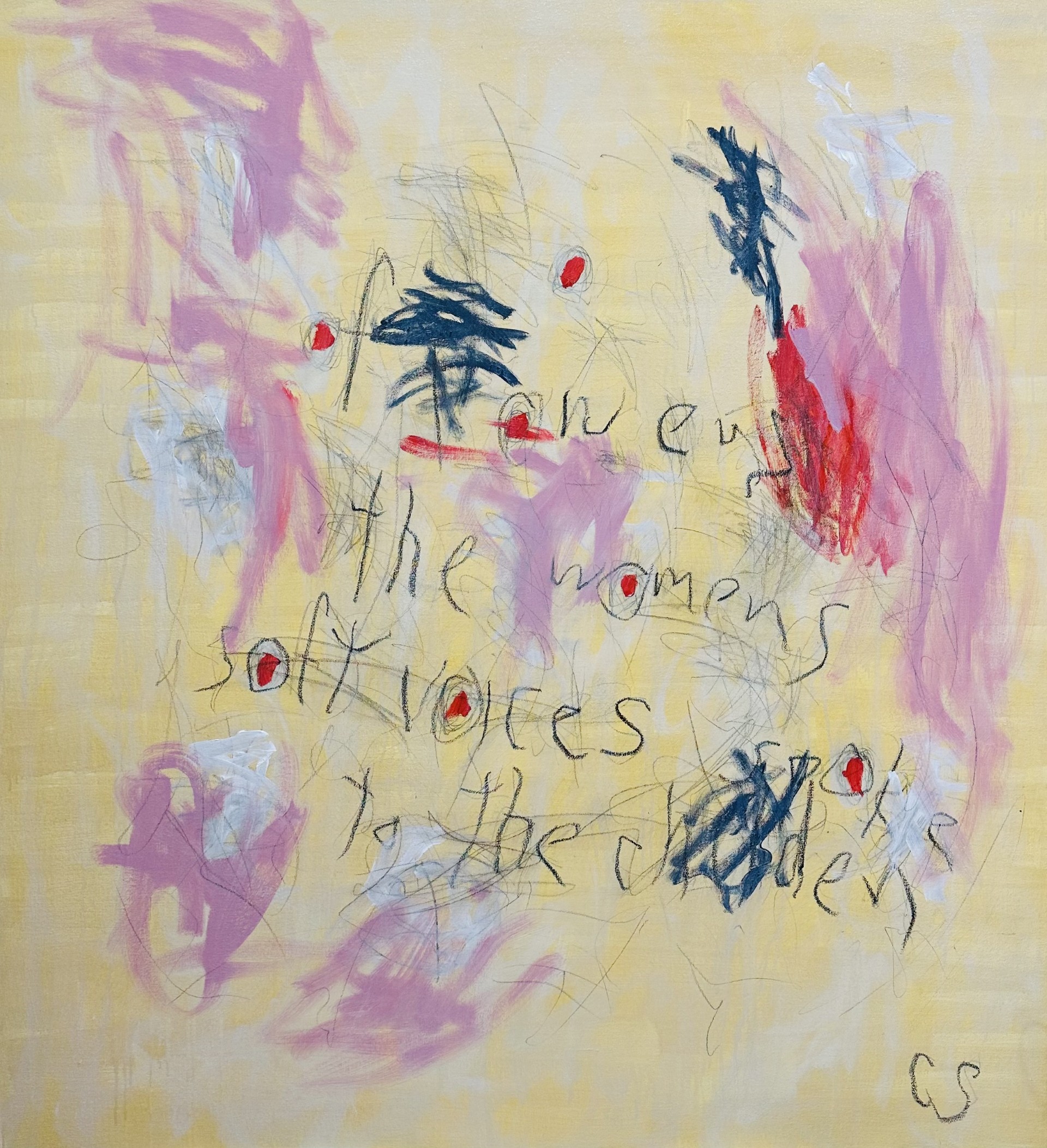

Having recently established a studio at Goolugatup, Cim – with her work 'The women's soft voices spoke to the children' – takes us on a journey between a daughter and her First Nations mother who was taken as a baby during the WA Government’s policies to ‘make them white’. Through her art, her mother’s love of wild flowers and connections to Country, Cim uncovers historical truths that leads her to reclaim her mother’s narrative, fight for her human rights, her dignity and her stolen identity.

Cim is the inaugural Goolugatup Studio Artist to be included in a rotational display of work in our reading area. Along with this display, artists are interviewed by University of Western Australia Curatorial Placement students as a part of their internship at Goolugatup. This reciprocal exchange between curatorial students and practising artists is an important avenue for inter-generational exchange along with skill and story sharing. Cim was interviewed by Lauryn Heath, and you can read the interview at Goolugatup, or in full below.

Image: Cim Sears, The women’s soft voices spoke to the children ,2025, acrylic, oil stick, oil pastel and graphite on canvas, 1.3m x 1.2m. Image courtesy the artist.

Lauryn: To start, please gives us a brief description of your practice, your preferred medium and subject matter:

Cim: My subject matter is mostly around my family history and my Mum, who was a Stolen Generation survivor [and] taken from the Station when she was one year old. I ended up finding the files back in 2005 – I didn’t know anything about that before – so it is really about bringing out the big story surrounding that through my art. While she was still alive, I was more tentative about bringing it up because for her it was very difficult to face, and I didn’t want to betray her in that way. But increasingly, I’m getting more brave about bringing aspects about it out.

I go to the Station where she was born which is about 1000 kms from here: it’s called Wongawol and I have been there 8 times now and each time I go I gather resources for continuing my art. Initially I did not know much, but […] The walls of the homestead have been scratched and gouged with names and a million stories. However, I started in the creek bed, where my people would sleep during the heat of summer. I took my copper plates and started scratching my plates using the rocks there […]

I initially started with Photography, studying at ECU, but switched to Visual Arts. I ended up enrolling in a printmaking course there with Paul Uhlmann. I loved printmaking because it is very close to photography. There is little difference [except] you are doing it in the day instead of in the dark. I started doing photography long ago in the darkroom and it was purely analogue.

I spoke to Paul Uhlmann, and he suggested getting my Master's degree, so that’s when I decided to do it around my Mum’s big story. I started that in 2017 and finished my Master’s in June 2020.

Lauryn: How did you come to have a studio at Goolugatup?

Cim: I used to look at this place on Instagram and follow the people who are here – never imagined that I would get here [Goolugatup]. After Uni, I enrolled in a printmaking session at Fremantle Arts Centre with a girl that I did my Master’s with. She was away one day, and Jo Darvall took the class. Jo is one of the founding members here [Swan River Print Studio] and she really liked what I did. Later, I was doing a photographic exhibition at Earlywork Gallery and Jo was there doing some printing. And she said, “Cim, you know you should really think about becoming a member.” So, that’s really how it all happened. So when the applications came out I applied, and I got in.

Lauryn: It’s one of those places that are just under your nose.

Cim: Yes, the place really came to me. I wasn’t sort of seeking it. But it’s a good fit for me.

Lauryn: Is your studio close and easy to get to?

Cim: Well, yes, I live in Mosman Park, so it doesn’t take me long to get here. I did have a residency at Fremantle Arts Centre for a year just before this, but that finished in April and I got into here in February. With the Swan River Print Studio, we just book online and you basically have the studio to yourself, so you can get a lot of work done and there’s not many of us.

Because I have my daughter and her baby living at home with me, I can’t get too much done, I get highly interrupted. So, I asked if they had any studio space available and finally, they said yes, we do. It’s a small space but it’s a space that I can work in and not be interrupted.

I have a big solo exhibition happening down at the Albany Town Hall in November [2025] and that’s why I am doing these paintings.

One of the aspects that I am working on now is trying to find the history of my Mother’s brother who we didn’t know existed. These paintings are basically like an honouring. When you go to a graveyard to find family, you see the Aboriginal people completely cover the grave site with artificial flowers which is quite incredible. When I found my Great Grandmother’s grave up at Wiluna, I took red silk flowers with copper stems and I ritualistically placed them all over her grave.

The graves are just mounds of dirt; they are not named. Now I am doing it for my Mother’s brother who is buried down at Pinjarra. I found out something recently that was pretty shocking. I am fine with it now, but it did hit me in the guts. It’s about Henry (my mother’s brother) and his best friend who were both at Moore River Native Settlement. They were working at the farm there and decided to go shooting. Henry unloaded a shotgun and as he unloaded and put it against the tree, it went off and shot his friend in the neck and killed him. That’s in Trove. But I haven’t been able to find much else about my mother’s brother […] They [a newspaper article collected by the artist] start off with “Half caste boy…”. That painting behind you has “half caste” written on it - and most of the inscription that’s in the article. This painting is like a memorial as I have not gone to the grave yet, but I think I can find it.

Lauryn: I can see how the story translates into your painting.

Cim: I kind of do things in an abstract, oblique way. Most people would not know what it’s about; it must be explained.

Lauryn: Especially because it’s your own story. Depending on who sees it, people may be able to relate.

Cim: Yes, it will be an interesting reaction because some people might relate to the colour, to the graphics, design or whatever, but then there’s this very serious story underneath it.

Lauryn: With what we have discussed and what I can see in this studio space is that your practice is a lot broader than printmaking.

Cim: Photography informs almost all of my work. For me it’s a bit like wax on, wax off. They all inform each other, whether it’s art, printmaking, photography, it’s all the same for me. I do ceramics as well. I did that because I wanted to replicate shapes in a photograph I saw of really early Western Desert Aboriginal people. Their perfect bowls were carved out of wood, which was really strange to me. I had never seen it before. I was just trying to immerse myself. A lot of my art is about immersing myself in the story, allowing the story to bubble up and reveal itself.

That’s what I was doing with ceramics. So, I went down to Freo Arts centre and spoke to Stewart Scambler and told him what I wanted to do. He said start making some maquettes first and then those maquettes ended up informing me. I don’t do the wheel. The wheel is not for me. I do hand building, so it’s very tactile and I can create beautiful shapes. I took some of my art and ceramics to the Station [Wongawol] and had an exhibition there. I put my ceramics over in the round yard and with the wind they filled up with red dirt. Then I found an old open fire and placed my bowls in there. All the red dirt that had flown into those bowls is still there today. So, it’s very much immersive and letting the elements speak to me. I’ve also got lots of archives, so it’s a bit of a puzzle for me; I have to piece together a lot.

Lauryn: It’s nice to hear that you have your hands involved with a lot of multimedia processes.

Cim: Even when I run the house, I do about six jobs at one time.

Lauryn: When you exhibit a show, do you display your multimedia works together or do you have solo medium exhibitions.

Cim: No, I display it all. For example, [exhibition at Gallery Central] for Mother – I had some large photographs and I had them beautifully framed. Then, I printed large photographs on Japanese handmade paper and I hung those as banners from the ceiling. Then, I had these things here: [points to works in studio], these are like mono prints. I did these at the Fremantle Arts Centre. They are on the Japanese Kozo paper. Some of them might have two or three processes. Here, that’s a photolithograph, then I’ll come over with colour. I was using mono printing, photo lithography and silkscreen printing and then there’s a photograph underneath that. So, there’s multiprocessing going on here. I usually just stack them and call them loose leaf books. My exhibitions are always multifaceted.

I did another exhibition called Yam. I was working in collaboration with two anthropologist friends of mine who know a lot about the Western Desert.

Interestingly, Wongawol Station where my Mum comes from, the main totem there is the Yam. It’s Yam country. Not that I have dug any of them up yet.

Lauryn: Have you always been an artist or have you worked or studied in a field that is quite different from what you do now?

Cim: Well, I suppose I was always an artist without being aware of it. I was good at it when I was in school and when I was younger. I was born in 1956, a long time ago. I went to boarding school and we didn’t have any resources. We didn’t even have an art room at that point. It just wasn’t like it is now. I never got any feedback about my abilities, so I never even thought about going to art school.

I ended up leaving school and getting a job in pathology as a laboratory assistant. I went all over the State taking blood which was a very varied and creative thing to be doing which [involved] multitasking because I would have to take the blood on the wards and then take it back to the laboratory. It was repetitive and really beautiful; you would also be painting the agar plates and watching the bacteria grow. They were all patterned and when you’re doing the blood testing, and in the centrifuge, it’s also patterned.

So, it really kind of suited me, plus I got to travel – I worked in just about every lab in WA. Some of them I was there by myself, and I was only 17. Then, I met my future husband in Port Hedland, and we travelled together for a year, basically hitchhiking around the world. We both saved 3000 dollars, and it kept us going for the whole trip. We jumped on a Russian Cargo ship to South America and then we were hitching on the back of trucks. We were away for a year and then I came back to study. I ended up doing Politics and Anthropology; I probably should have done art. But still, it was not something that was in the front of my mind.

After having my second child I became a social worker, I worked in Women’s health and in hospitals. But it was only when my third child refused to go to daycare I had to switch tack, I had a little break and then started going down to Fremantle Arts Centre. I studied with Larry Mitchell. I first did watercolour with Peter Walker, and he said to me, “Cim, you can draw, you better go see Larry [Mitchell]” and so I booked into his classes for the next three years doing oils.

[Larry] is the guy that does the Abrolhos paintings. Since then, I went to TAFE and did photography because I was interested in that. Along the way there has been a lot of self-teaching, but with beautiful mentors also along the way. I did workshops with George Haynes. He is part of the Art Collective in town. His use of colour and his knowledge of perspective is unbelievable. Larry Mitchell always referred to him. I [also] did a lot of workshops with War photographers. I would go around the world with them. I went to Cuba, Kathmandu, Sydney and here. That’s when I enrolled at ECU after looking at courses which were predominantly art based, creative based and ECU seemed to fit me.

Lauryn: I think ECU is one of the only universities here in WA that have a dark room, correct?

Cim: Yes, they do analogue. I can tell you that photography is such a good grounding and base. It teaches you a lot and you can use it across the board for all other things you do. It’s really good training. The framing up, composition, tonality, all that sort of thing.

Lauryn: So, you were always an artist without realising it […]

Cim: yes, I used to paint in all our books growing up (you know my Snugglepot and Cuddlepie still have all my marks in them). I used to go around all the skirting boards and the light switches with pen.

Lauryn: Art was always there for you. You mentioned that in your first degree and job as a pathologist had art in there too. Did you find that, since you had your pivotal moment of finding art a bit later in your career, did that other degree and your job in pathology intertwine and inform each other?

Cim: Yes, I think so. It’s been a long journey and I haven’t really been conscious of it; of how it’s informed me but when you look back on it, it certainly has. It’s a sort of mix using the elements of the earth and going out to the [Wongawol] Station and to the Desert Country to bring up the stories that seem to have been suppressed for so long.

Lauryn: As you have travelled a fair bit to the Western Desert, how does your art practice in the outdoors on country look different to your studio space practice? Do you have a preference?

Cim: The difference is four walls. But at least I know I can go out there. And here, there is the quiet space I need to create, so it’s great to have both. But the outdoors is where I get a lot of my materials and inspiration, but I also gather from the archives.

Lauryn: It’s interesting as you did mention that the rocks you use to scratch into those copper plates, and the wire is accumulated from sites in the Western Dessert. Is it hard to prepare for a trip like that?

Cim: Not now. With this recent one, my daughter’s partner kindly cleared up my art room, but then I couldn’t find any of my cameras, so this time I just took out my Instamatic Polaroid, and I really like the effect it gives me. I use my iPhone a lot too. I’ve got a big Nikon D3 and D700 which are both very nice cameras. But these days, the iPhone is really simple, and I am usually turning my photographs into something else anyway.

Lauryn: For one of your exhibitions called I Walk to See, I Walk to Know: Walking to Wongawol you said that you were able to discover ancestral connections that were historically erased by the state. How has art played a significant role in this area of discussion, and do you think art has an effective drive to unfold these truths?

Cim: Well, it’s integral really, it’s through mark-making and scratching that the stories start to bubble up and get revealed. So even if I don’t really know what’s going on, I can take myself there and collect bits and pieces. I might only have a thread of the story but somehow you can scratch them up, literally and metaphorically.

I’ve always felt I am the centre of my art, I’m not separate from it, so when you feel like that, you have faith in knowing that whatever you produce is part of the story even if you don’t quite understand it. And one thing might lead to another. Sometimes you just need to start doodling. Even with these paintings, I knew I couldn’t get to the grave site and get to decorate the graves, so I used these paintings to do that.

Lauryn: As you have an exhibition coming up, how else do you plan to use this space at Goolugatup?

Cim: To do what I already do, just be able to come here and immerse myself and just put on another layer of paint or start a new painting. I feel really lucky to use this space. Even though I use my whole house as a studio, with a 20-month-old baby it’s a bit difficult, although I could just let her scribble on my paintings as well and I’d be fine with that. She would just add to them.

Interviewer: Lauryn Heath

Artist interviewee: Cim Sears

Lauryn is a third-year UWA student currently obtaining her Undergrad degree in Curatorial Studies and Art History. At Goolugatup, she completed an internship placement through the UWA Curatorial pathway.

Goolugatup Heathcote is located on the shores of the Derbal Yerrigan, in the suburb of Applecross, just south of the centre of Boorloo Perth, WA. It is 10 minute drive from the CBD, the closest train station is Canning Bridge, and the closest bus route the 148.

58 Duncraig Rd, Applecross, Boorloo (Perth), Western AustraliaOpen 10–4 Tuesday–Sunday, closed public holidays. The grounds are open 24/7.